Background

As has been stated before, Docker containers do not contain all of the parts of the operating system necessary to be considered secure. That said, the advantages of using them is so compelling that many companies, large and small, have began to investigate how to run containers in a production environment. I would argue that it can be done, but careful thought must be given to security and best practices.

Everyday, people ask me for guidance on how to best run Docker containers, how to determine what can be run in a container, and how to do it in a secure and manageable way. SELinux and sVirt are a key technology for running Docker in a secure way. Historically, SELinux is something that people just turned off, but this article will focus on running Docker containers with SELinux in enforcing mode.

People have been downloading and running software off the Internet for as long as it has been around. History repeats it’s self, so this article will also focus on why you need to think about where your Docker images come from and what is inside of them.

Securing Docker Containers

The Circle of Trust

When I first started running Docker containers in RHEL6, I wasn’t extremely worried about sVirt or SELinux. This is because my use case was typically Docker images which I built myself from OS instances which I installed and also built myself. As we move to production workloads, this has all changed.

This brings up an import concept called the circle of trust. We don’t often think about it explicitly, but whenever we take actions we implicitly rely on the circle of trust. Like Greg, in Meet the Parents, when I downloaded and installed RHEL from the ISO file, I let Red Hat into the circle of trust.

Jack Byrnes: But the fact is, Greg, with the knowledge you’ve been given, you are now on the inside of what I like to call… “the Byrnes family circle of trust.” I keep nothing from you, you keep nothing from me…and round and round we go.

Greg Focker: Okay. Understood.

Jack Byrnes: Okay, good. Come on. Let’s go inside and have breakfast.

Going a step further, each of the following steps expands the circle of trust. In my particular use case, I did the OS installation, configuration, and preparation. I created a tar ball, and performed a Docker export. I then uploaded the image I created to our internal registry server. Finally, I publicized and shared the image with other people here at Red Hat. It is useful to realize that other people in the circle of trust are relying on you to create images in a manner that makes them useful and trustworthy.

1. ISO Download

2. Verify check sums

3. Install OS

4. Prepare OS for imaging

5. Create Docker image

6. Upload to internal registry server

7. Share with others

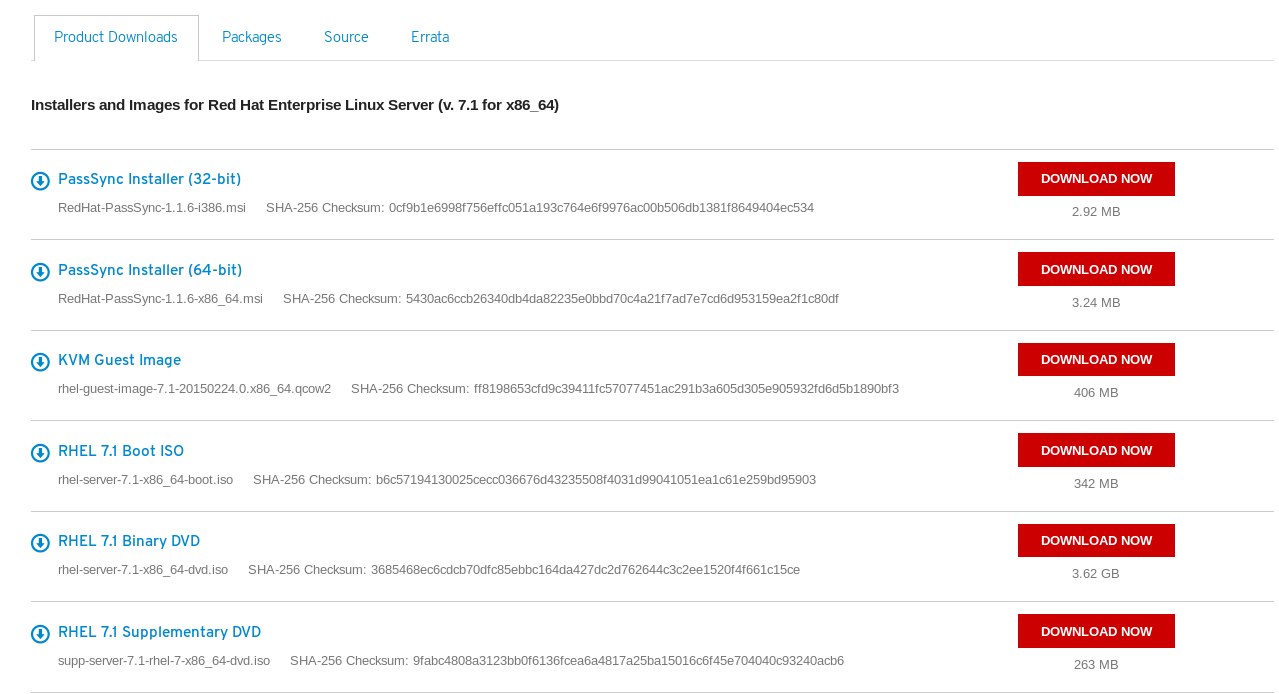

There are a couple of key points in the circle of trust, or software supply chain. First, I went and downloaded the binary from Red Hat’s site. Notice the SHA-256 keys. This is a technical implementation to safely expand the circle of trust. Image signing and verification is not yet ubiquitous in the Docker image spec, but it is something that is being actively worked on within the Docker project and the Appc project.

In the last six months my use case has expanded to include the certified RHEL6 and RHEL7 images provided by Red Hat. In this case, I have simplified my workflow to the following:

docker run registry.access.redhat.com/rhel6

docker run registry.access.redhat.com/rhel7

docker push 10.0.0.33:/rhel7-corebuild

From a process perspective, this has simplified what I do to the following.

1. Pull Docker image

2. Customize the image

3. Upload to internal registry server

4. Share with others

This workflow led me to a couple of conclusions about trust. When I go out and download the ISO or Docker image, I trust Red Hat Engineering to create something I can trust. I then make changes to create a core build, preferably using a Dockerfile. Finally, others in my team download the image because they trust me and my methods. Circle of Trust!

Outside the Circle of Trust

My original use case on RHEL6 was really about running things from within the circle of trust, but what happens when we run something from outside the circle of trust? That’s where SELinux and sVirt in RHEL7 and Atomic Host become important.

Red Hat definitely recommends running Docker containers on RHEL7 because of capabilities like sVirt. Notice, from the following command ran in RHEL6, that sVirt is not enabled.

ps -efZ | grep docker

system_u:system_r:initrc_t:s0 root 5639 1 0 May01 ? 00:00:15 /usr/bin/docker -d

unconfined_u:unconfined_r:unconfined_t:s0-s0:c0.c1023 root 7350 7400 0 17:44 pts/0 00:00:00 grep docker

unconfined_u:unconfined_r:unconfined_t:s0-s0:c0.c1023 root 19252 16331 0 May20 pts/6 00:00:00 docker run -t -i 10.3.76.138:5000/rhel7-base bash

Both of the Docker containers use the same SELinux Context. This means that processes in the container are not isolated from each other or the host OS.

unconfined_u:unconfined_r:unconfined_t:s0-s0:c0.c1023

In RHEL7 two types of enforcement occur: Type Enforcement (lxc_net) and MCS Enforcement (s0:c340,c388). These protect the containers from the host and from each other. For a deeper dive, check out Dan Walsh’s article.

ps -efZ | grep -v kernel| grep svirt

system_u:system_r:svirt_lxc_net_t:s0:c340,c388 root 62797 1027 0 May20 pts/1 00:00:00 bash

system_u:system_r:svirt_lxc_net_t:s0:c534,c1022 root 66145 1027 0 May20 pts/4 00:00:00 bash

Notice that each of the containers has the same type, but different MCS Labels (aka sVirt). The type determines general capabilities (files, network ports, process). The MCS label, separates the contaiers from each other and are automatically generated when the container is started. This ensures that each container only has access to data structures with a matching label. Think disk, network, etc….

cat /etc/selinux/targeted/contexts/lxc_contexts

process = "system_u:system_r:svirt_lxc_net_t:s0"

content = "system_u:object_r:virt_var_lib_t:s0"

file = "system_u:object_r:svirt_sandbox_file_t:s0"

sandbox_kvm_process = "system_u:system_r:svirt_qemu_net_t:s0"

sandbox_kvm_process = "system_u:system_r:svirt_qemu_net_t:s0"

sandbox_lxc_process = "system_u:system_r:svirt_lxc_net_t:s0"

The Future

Dan Walsh is working on a patch to allow an administrator to run the Docker container with an arbitrary label. Imagine running Docker with the following options:

docker run -ti --security-opt label:type:lxc_nonet_t rhel7 /bin/sh

While running different Docker containers with different labels would be less convenient, it could be managed with SystemD, Kubernetes, etc, and would allow administrators to created highly regulated SELinux Policies. For example, administrators may create custom labels such as:

type:lxc_nonet_t

type:lxc_web_t

type:lxc_ftp_t

type:lxc_dns_t

If for example a DNS container was hacked, it would not be able to serve web traffic for a hacker. It would even be possible to create a container that didn’t have any network access (lxc_none). Customized labels are a powerful tool to prevent privilege escalation should a container become compromised.

Conclusions

If you combine trusted images with sVirt, the risk of running containers in a production environment can be reduced to an acceptable level.

Jack Byrnes: Greg, a man reaches a certain age when he realizes what’s truely important. Do you know what that is?

Greg Focker: Love… friendship… enjoying the moment… living… just love.

Jack Byrnes: His legacy.

Greg Focker: That, too. Right, yeah. Sure.

Jack Byrnes: Let me put it very simply. If your family’s circle does indeed join my family’s circle, they’ll form a chain. I can’t have a chink in my chain.

We at Red Hat, welcome you to join our family circle of trust, together we will create a secure, open source chain of trust 😉

There is an exciting future here and I leave you with the Circle of Trust Montage

4 comments on “Securing Docker Containers with sVirt and Trusted Sources”